Overview

Unit 1 will provide you with a general introduction to inquiry, familiarizing you with foundational concepts related to scholarly inquiry. In particular, this unit will focus on the philosophical foundations of research, the connection between leadership and scholarly inquiry, and what evidence-based leadership looks like. By the end of the unit, you will understand the importance of research and begin to evaluate the decision-making processes that you utilize in your professional life.

Topics

Unit 1 is divided into 4 topics:

- What is Scholarly Inquiry?

- Leadership and Scholarly Inquiry

- Philosophical Foundations of Research

- The Research Process

- Asking a Research Question

Learning Outcomes

When you have completed this unit you should be able to:

- Distinguish between informal research and scholarly inquiry.

- Reflect on why evidence-based decision making is important for leadership.

- Identify a research interest and develop a good research question.

Activity Checklist

Here is a checklist of learning activities you will benefit from in completing this unit. You may find it useful for planning your work.

Resources

Here are the resources you will need to complete the unit:

Text:

Rosch, D. M., Kniffin, L. E., & Guthrie, K. L. (2023). Introduction to research in leadership. Information Age Publishing.

E-Resources The articles below can be found through the TWU library

- Brown, M.E., Dueñas, A.N. (2020). A medical science educator’s guide to selecting a research paradigm: Building a basis for better research. Medical Science Educator, 30, 545–553. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-019-00898-9

- Wallace, J. R. (2007). Servant leadership: A worldview perspective. International Journal of Leadership Studies, 2(2), 114-132. https://www.psychodramaaustralia.edu.au/sites/default/files/serveant_leadership_-_worldview.pdf

All other resources will be provided online.

1.1 What is Scholarly Inquiry?

Inquiry is “the process of developing skills to arrive at understandings of a problem, an issue, or a phenomenon, through the process of asking good questions, searching out good evidence, and arriving at well-reasoned conclusions” (Penner, 2017).

By now you are well aware of the applied nature of the MA in Leadership program. This feature may be an important part of what attracted you to the program! Why then study research methods? Why worry about scholarly inquiry? This course in scholarly inquiry will help you to develop systematic thinking skills applicable in all realms of leadership and everyday life. As Rosch, Kniffin, and Guthrie (2023) note, research focuses our professional knowledge, to inform your leader-centric, group-centric, and context-centric to guide the broader view of our leadership position and contributes to our ocverall leadership practice (p. 23). Moreover, our leadership practice is ideally evidence-based; that is, based on evidence derived from systematic scholarly inquiry.

1.1.1 Learning Activity

1.2 Introduction to the Reflective Journal

A reflective journal is simply a record of your thoughts. There is no correct way to create this journal; rather, it is a reflection of the way you think and the manner in which you respond to your learning. Journals can consist of traditional note taking on paper, or in a word document, you can create mind maps, pictures, or just write stream-of-consciousness, you can record your thoughts in an audio file, write down important quotes, create sketches, or drawings: whatever you choose to include. Experiment and have fun.

The purpose of journaling is to make you an active participant in your learning experiences as you engage in the various activities throughout the course’s readings, activities, and discussions with your instructor and your fellow students. Reflecting upon these learning events will help you gain a deeper understanding of the course materials and help integrate your learning into applied practice in your everyday life and work.

Throughout the course, we will remind you to write in your journal, as we want to be sure you are actively learning the material. To assist you, we have provided you with questions you can ask yourself in order to get your creative energies flowing. Reflective journaling is an activity you can and should complete on a regular or daily basis, even outside of our scheduled course activities.

Common Questions Used for Reflective Journaling

- In your view, what were the most important points in the readings, videoclips, or discussions with your fellow students and tutors?

- What information did you already know?

- What new knowledge, ideas, or perspectives have you gained?

- What information was easy to remember or learn? Why?

- What concepts did you find more difficult? Why?

- How can you apply this knowledge to your work or current experience?

- How has this knowledge helped you to make sense of your current or previous experience?

- Has your understanding of a personal or work-related situation changed after studying these concepts?

- Did you agree or disagree with any of the material? If yes, how did you react and why?

- If you could have the opportunity to engage in further learning, what would it be?

- What further questions would like to ask the author of your readings?

- What other articles, books or discussions would be of interest?

This journal is not submitted or graded, but is an opportunity for you to reflect on, and engage with, the course content. The questions posed will often help you prepare for your assignments and are designed to help you successfully achieve the learning outcomes for each unit.

1.3 Leadership and Scholarly Inquiry

On what basis are sound decisions made? What evidence do leaders rely upon for best outcomes? The need to evaluate evidence for best practices in leadership decision-making is widely acknowledged. Patton (2001) observes that “the emphasis on knowledge generation disseminated in the form of best practices has swept like wildfire through all sectors of society” (p. 329).

We often refer to the vision of best practices in leadership within the MA in Leadership program. What do we mean by this? Put simply, “best practices” refers to those practices and initiatives that result in the best possible outcomes. How do we know what best practice is? The process of identifying best practices begins with an understanding of common sources of evidence available to leaders.

Take a moment to think about a recent decision you made as a leader. On what did you base this decision? Previous experience? Values? Company policy? Empirical evidence (e.g., data derived from research)? Expert opinion? Systematic inquiry (as represented by research) is one tool that leaders can use to inform best practices and their decision making process.

Systematic inquiry is hardly new – in first century writings we see in the Bible evidence of systematic, logical, and empirical inquiry. Consider the following passage from Luke, a physician trained in empirical methods of his day:

Many have undertaken to draw up an account of the things that have been fulfilled among us, just as they were handed down to us by those who from the first were eyewitnesses and servants of the word. With this in mind, since I myself have carefully investigated everything from the beginning, I too decided to write an orderly account for you, most excellent Theophilus, so that you may know the certainty of the things you have been taught. (Luke 1:1-4, NIV)

How does the research process differ from managerial activities such as decision-making and problem solving? Research shares with decision-making and problem-solving the systematic and disciplined procedure of identifying an issue/problem, deciding on an approach, formulating a plan, collecting and analyzing data, drawing conclusions and implementing decisions based on this rigorous process. What distinguishes research from generic or everyday problem solving is its commitment to advance or generate knowledge that typically will be communicated to the larger academic or scientific community. The past two decades have produced remarkable growth in the area of foundations of research and research methodologies within natural, applied, and social sciences and humanities.

Boyer’s Model of Scholarship

The Master of Arts in Leadership program is focused on applied scholarship. In defining this, Boyer’s four-part Model of Scholarship (1997) is useful. Boyer’s typology identifies four domains of scholarship: discovery, integration, application, and teaching. The model is discussed by Marta Nibert (2011) in her paper titled Boyer’s Model of Scholarship. In the section titled Application she notes that the scholarship of

. . . application, focuses on using research findings and innovations to remedy societal problems. Included in this category are service activities that are specifically tied to one’s field of knowledge and professional activities. Beneficiaries of these activities include commercial entities, non-profit organizations, and professional associations. (para. 4)

Though Nibert’s primary audience is the professoriate, this material is relevant for MA in Leadership learners. Application is highlighted because the Master of Arts in Leadership was designed to focus primarily on the scholarship of application, although work in the capstone will likely include one or more of the other domains.

Boyer’s Scholarship of Discovery is the type of scholarship associated with traditional scholarly research. “Research is a systematic process of collecting, analyzing and interpreting information (data) in order to increase our understanding of a phenomenon abut which we are interested or concerned” (Leedy & Ormrod 2010, p. 2).

Boyer’s Scholarship of Discovery is often referred to as primary research. Primary research is narrowly focused, and contributes to the body of knowledge by helping us to understand one isolated part of reality in detail in the hopes that this understanding can be generalized to some degree to a broader part of reality. The Scholarship of Discovery (in traditional research) falls into two distinct genres: quantitative research and qualitative research. Each of these genres manifest in numerous variations, including hybrid models involving both quantitative and qualitative elements, designed for and suited to differing research questions.

Boyer’s Scholarship of Integration is “the attempt to arrange relevant bits of knowledge and insight from different disciplines into broader patterns that reflect the actual interconnectedness of the world” (Boyer cited in Jacobsen & Jacobsen, 2004, p. 51). Scholarship of Integration often demands interdisciplinary collaboration and requires that the critical analysis and review of knowledge be followed by the creative synthesis of views and insights in such a way that what is known speaks to specific topics or issues.

The Scholarship of Application is “the scholarship of engagement; seeking to close the gap between values in the academy and the needs of the larger world” (Boyer cited in Jacobsen & Jacobsen, 2004, p. 51). In the Scholarship of Application, knowledge is applied to the solution of societal needs and practice. In most cases, knowledge stemming from the Scholarship of Discovery and the Scholarship of Integration informs the solutions to particular problems. The Scholarships of Discovery and Integration are often associated with the context of formal education. The Scholarship of Application may happen within formal education contexts, it is most often associated with other settings (Bosher 2009, p. 6).

Finally, the Scholarship of Teaching is “the scholarship of sharing knowledge” (Boyer cited in Jacobsen & Jacobsen, 2004, p. 51). The Scholarship of Teaching involves the reflective analysis of the knowledge about teaching and learning. This knowledge base itself is the product of the Scholarships of Discovery, Integration and Application combining as “active ingredients of a dynamic and iterative teaching process” (Bosher, 2009, p. 5).

Boyer’s typology originally identified as the Scholarship of Teaching has been expanded somewhat and is widely known today in the literature as the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (Bosher, 2009). You have undoubtedly already noticed an ambiguity: If the entire model is called the Scholarship of Teaching, how is it that the last element depicted in the chart above is also called the Scholarship of Teaching? This ambiguity is evident, Bosher contends that Boyer’s four domains were conceived holistically as elements that overlap and interact, not as discrete elements, appearing in any predictable order, and are better viewed as an operating system than a list of discrete elements (2009, pp. 4-5).

1.3.1 Learning Activity

1.4 Philosophical Foundations of Research

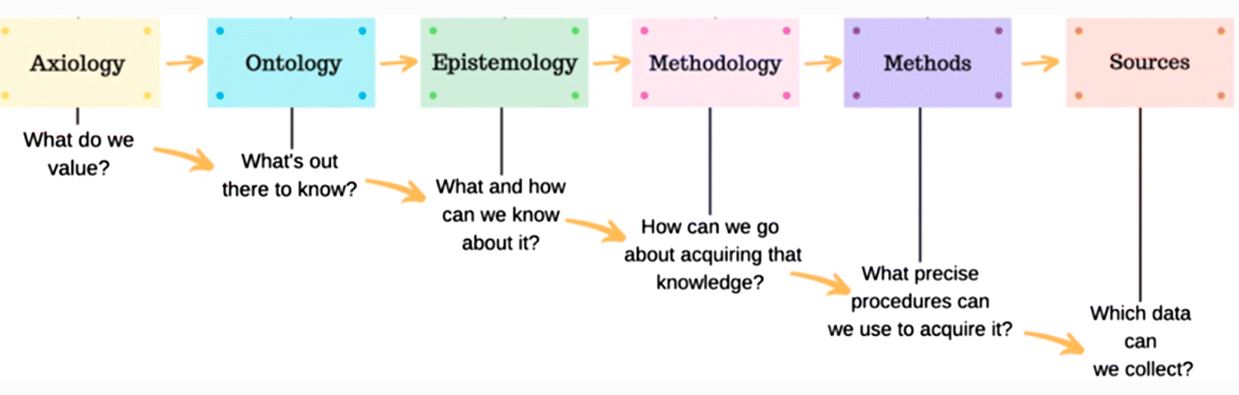

A professor of mine often observed that a fundamental attribute of being human is to ask questions. Humanity is especially interested in three fundamental questions: What is real? What is true? What is good? The philosophical category of metaphysics is concerned with what is real, and what is the nature of reality. The philosophical category of epistemology is concerned with what is true, and what is the nature and process of knowing. The philosophical category of axiology is concerned with what is good and how we can determine the nature of goodness. Much of history is a chronicle of the different ways people have answered these three fundamental questions. How we answer these questions reveals our perspective, or our worldview.

Every person bases his or her own thoughts, decisions, and actions on what is called a worldview. A worldview is “an interpretive framework through which one makes sense of themselves, other people, and the world around them” (Geisler & Watkins, 2003). It is like a pair of glasses that you wear when you are observing things about yourself, other people and the world in which you live. Here is a short video by the Impact 360 Institute (2014) that explains “What’s your worldview?”

A discussion about worldview, or your perspective, is foundational to what we want to accomplish in this course. Throughout this course I will ask these questions: On what basis are sound decisions made? What evidence do leaders rely upon for best outcomes when they are making decisions? Each of us has a preference for obtaining truth or a framework for understanding ourselves, others, and the world, and personal preferences abound. Researchers and consumers of research (i.e. us) approach knowledge and learning and life with a certain perspective and it is important to understand that perspective before you jump into the research journey and it is certainly something to consider in positions of leadership.

Here is a really helpful video by Laura Killam (2013) that explains Paradigms, Ontology and Epistemology.

It is important to be aware of your worldview before you enter into the research journey because it will inform the types of questions that you ask as well as the processes that you use to find the answers to your questions. As an example, let me explain a Christian worldview and explore how this worldview can be applied to the research journey.

A Christian worldview asserts that God has created the world and everything in it, and that truth is arrived at through a study of God’s specific revelation (the Bible) and general revelation (creation). Christians believe not only in studying and understanding truth, but they also believe in a personal God that has revealed Himself through this created world.

The Christian worldview can be summarized in three words: Creation, Fall and Redemption. Let me unpack these terms. Initially, when God created the world, it was all good and whole and harmonious. God created man in His own image. Originally man was created healthy in body, soul and spirit (Genesis 1:26-27, 31). As people rebelled against God, causing the Fall, the presence of sin corrupted all aspects of God’s good creation, and brought about much suffering. Where there was formerly harmony and wholeness, we now experience ourselves, our relationships and the world around us as fractured, broken and full of dis-ease (a literal discomfort with who we are) (Genesis 3).

Despite the brokenness, Christians believe that God is actively working to bring about restoration and wholeness to His entire creation. Through Christ’s redemptive work on the cross, people are reconciled to God and are challenged to make all things as they were created and meant to be – very good. Redemption means that all things are made new in Christ (Colossians 1:19-20).

The framework of Creation, Fall and Redemption is important because it allows us to enter into a discussion about research with confidence knowing that God’s redemptive work touches this area. Christians believe that we are called to study creation with the desire to take the knowledge we gain and use it to help and bless others; to work toward the restoration and healing of God’s creation. Christians are called to inquire, to investigate, to ask questions, always with a view to serve others.

It is beyond the purpose of this course to go deeper into this topic other than to make the point that our way of knowing and understanding the world around us (i.e., our worldview) influences how we approach all of life, including how we approach research and how we use research to inform our decision-making process.

1.5 The Research Process

Plano-Clark and Creswell (2015) define research as “a process of steps used to collect and analyze information in order to increase our knowledge about a topic or issue” (p. 4). Plano-Clark and Creswell (2015) identify eight steps in the research process which provide us with a useful framework that describes what researchers do when they conduct their studies. These steps help us understand the information that is included in their reports. Listed below are each of the eight steps in the research process.

- The whole process begins with identifying the research problem. This step is vitally important. The statement of the research problem is the very foundation that subsequent research is built upon, and quite literally guides each and every step moving forward.

- A literature review is a summary of the “state of knowledge” in a given area. This step is the primary focus of this course and involves locating relevant scholarly literature, and analyzing, synthesizing and summarizing what precedent literature has to say about a specific topic.

- The purpose of research includes identifying the objective of a study (e.g., purpose statement). This information is typically expressed in a few research questions or hypotheses.

- Next, it is important to choose a research design. This step involves describing an overall plan or approach of the study and also explains the methods used to carry out the plan.

- Selecting participants and collecting data includes who will be the participants, how you will collect information from those participants, and what permission you need to obtain in order to collect the information.

- Analyzing data involves systematic processes to make sense of the information that has been gathered. We call this process “results,” which are then reported in forms appropriate to the research method (e.g., statistics or words).

- Drawing conclusions means interpreting the results and explaining how the conclusions relate to the research questions/hypotheses, and/or similar studies. There is also a discussion of limitations of the study and often suggestions of implications for the intended audiences, for practice and for future research.

- Disseminating and evaluating the research. Usually the term “disseminated” means “published.” The most common way that research is disseminated is in journals dedicated to publishing primary research.

1.5.1 Learning Activity

1.6 Asking Significant Questions

The most important part of the research process is beginning with a good research question. This is something that will be highly relevant to completing of most of your assignments in this course.

The research process often starts when you ask a question about something that you observe: How, What, When, Who, Which, Why, or Where? Questions can be based on what you observe in the real world, or on intuition or a “gut feeling”.

The question that you select is the cornerstone of your work in this course. The assignments you will be working on will revolve around finding an answer to the question you are posing. It is important to select a question that is going to be interesting to work on for the length of this course and a question that is specific enough to allow you to find the answer.

The Higher Education Academy and Sheffield Hallam University (2005) have developed an excellent guide for Formulating the Research Question. According to the authors, good questions are:

Relevant: The question will be of interest to people in your field and arise from issues raised in the literature or in practice. You should be able to establish a clear purpose for your research in relation to the chosen field. For example, are you filling a gap in knowledge, analyzing professional practice, monitoring a development in practice, comparing different approaches?

Manageable: The question you ask must be within your ability to tackle. For example, are you able to access people, statistics, or documents from which to collect the data you need to address the question fully? Can this data be accessed within the limited time and resources you have available to you? Sometimes a research question appears feasible, but when you start your literature review, it proves otherwise.

Substantial and (within reason) original: The question should not simply copy questions asked in other papers. It shows your own imagination and your ability to construct and develop research issues. And it needs to give sufficient scope to develop into a research paper.

Clear and simple: Getting this clear and thought-through is one of the hardest parts of your work. If you create a clear and simple research question, you may find that it becomes more complex as you think about the situation you are studying and undertake the literature review.

Interesting: This is key! The question needs to be one that interests you and is likely to remain intriguing for the duration of the project. There are two traps to be avoided. Make sure that you have a real, grounded interest in your research question, and that you can explore this in an academic paper. It is your interest that will motivate you to keep working and to produce a good research paper.

1.6.1 Learning Activity

1.7 Summary

In this unit you have learned about what scholarly inquiry is, what is a worldview and how it can shape the questions that we ask. You have also learned about the importance of scholarly inquiry for leadership, the implications of evidence-based decision making for leaders, and how to develop a good research question.