This unit investigates the nature of educational experience, and how to guide it within the emerging learning settings where the teaching presence is now being distributed across multiple modalities and instructional roles. In this emerging model there is a systematic division of labour of the traditional teaching responsibilities. For instance, in one emerging model of multi-access education the teacher designs a course and assesses the students’ learning. However, the work of facilitating and directing the social and cognitive processes for the purpose of realizing the learning outcomes is now the responsibility of learning coaches and facilitators.

Topics

This unit is divided into the following topics:

- What is Educational Experience?

- What Makes a Learning Experience Educational?

- Study as the Site of Education

- The Institutionalization of Teaching and Learning

- Emerging Models of Open and Multi-Access Education

- Multi-Access Learning Environments

Learning Outcomes

When you have completed this unit, you should be able to:

- Describe the characteristics of educational experience.

- Analyse the characteristics that make a learning experience educational.

- Identify the ways institutional learning and teaching is changing.

- Understand the difference between pedagogy and modality.

Resources

Online resources will be provided in the unit.

Topic 1 - What is Educational Experience

Earlier we were introduced to the idea that a learning environment can be understood as overlapping presences: cognitive presence, social presence, and teaching presence. In this unit, we explore what is experienced within this environment by examining the theoretical ground the CoI model is built upon.

The community of inquiry model is based on the broadly promoted idea within the contemporary field of education that people learn through experience—their own and the experience of others. What is experience? In the broadest sense, experience is a personal lived encountering, or undergoing, of some event. In this way, a person might say that they have experienced running, a recreational activity some people enjoy. Accordingly, this person might describe their experience as the physical sensations going on in their body and also their perceptions of what is going on in the world when they are running. Their experience in this case may be considered beyond the mere physical, and also include the emotional, cognitive, volitional, spiritual, or any of number of other characterizations of human nature. This experience denotes a form of knowing. In this sense, the person might say that they have experience in running, or that they are an experienced runner. Conceptions of experience as knowledge span a diverse spectrum of ways of knowing from empiricism to existentialism. Thinking about what it truly means to know through our experience, and how we gain experiential knowledge is fundamental to education.

The American pragmatist philosopher John Dewey (1916/2004) argues in Experience and Education that our concept of experience is essential to education, because “education is a development within, by, and for experience” (Chap. 1). Experiential knowledge is frequently assumed to be procedural rather than propositional. In keeping with this line of thinking, Dewey (1915) states, “no book or map is a substitute for personal experience; they cannot take the place of the actual journey” (p. 255). Dewey’s statement echoes the oft-quoted Chinese proverb by Xun Zi:

“Tell me and I will forget. Show me and I may remember. Involve me and I will understand.”

However, this is a limited understanding of experience as Dewey (1915) goes on to clarify,

“learning by doing does not, of course, mean the substitution of manual occupations or handwork for text-book studying” (p. 255).

His point, here, is that the studying of texts is also an “experiential learning” activity. In short, experiential knowledge is both procedural and propositional in nature. What is important to our discussion in this course is simply the fact that, clearly, we learn through experience—our own and the experience of others, through direct observation and conversation, and indirectly through mediated forms, notably written texts. This raises a key question, what is experience that we may say we learn through it? Or simply, what is educative experience?

According to Dewey’s theory of education and experience, one’s learning experience arises from the interaction of two essential principles—continuity and interaction. Continuity refers to his idea that each experience one has will influence, in some way, one’s future experiences. Building on continuity, interaction expresses the relationship between one’s past experience and present learning situation.

Put different, every experience that a learner enacts or undergoes modifies that learner, and this modification (whether the learner likes it or not) affects the nature, quality and direction of the learner’s subsequent experiences. In this way, then, we may come to speak of a person growing, developing, or transforming not merely physically, but intellectually, morally, and so forth. This idea of growth expressed within the principle of continuity also suggests direction, ends, or outcome.

For instance, we say learners “grow” to become experts (in something). Indeed, “expert” and “experience” are both derived from the same Latin verb (meaning “to test, or to prove”). Thus, by expert, we mean one tested and/or proved by experience. For instance, as a facilitator of a university course, your prime directive is to guide learners though learning experiences that ultimately lead to the learning outcomes prescribed in the course syllabus. Put in Dewey’s theoretical terms, we might say one thing you are trying to facilitate within the learning environment you create is the continuity of your students’ learning experiences, such that their experiences result in their transformation in some way that demonstrates the course learning outcomes. This idea is critical to your role as facilitator.

While a learning experience is something internal to a person, shaping attitudes, desires, purposes, understandings, and knowledge, it also has an active side that “changes in some degree the [world of persons and things within] … which experiences are had” (Dewey, 1938, p. 39). That is, as Dewey (1916/2004) writes elsewhere, “when we experience something we act upon it, we do something with it; then we suffer or undergo the consequences” (p. 133). Dewey suggests that one acts within a world and one’s world acts upon them. The principle at play here is the interaction of experience.

“An experience is always what it is because of a transaction taking place between an individual and what, at the time, constitutes his environment.” – (Dewey, 1938, p. 43)

Here, environment refers to “whatever [external] conditions interact with personal needs, desires, purposes, and capabilities to create the experience which is had” (Dewey, 1938, p. 44). As a facilitator you guide students’ interaction with their learning environment, according to the course designer’s intentions.

Taken together Dewey describes the interplay of his two principles of experience—continuity and interaction—as a learning situation. These two aspects of the learning experience, then, “intersect and unite,” as a learning process wherein “as an individual passes from one situation to another, his world, his environment, expands or contracts” (Dewey, 1938, p. 44). The value of one’s experience, may be judged according to the positive or negative effect that it has on one’s present and future.

Dewey describes the mechanics of the interplay of continuity and interaction as a trial and error learning process. He states, “We simply do something, and when it fails, we do something else, and keep on trying till we hit upon something which works, and then we adopt that method as a rule of thumb measure in subsequent procedure” (Dewey, 1916/2004, p. 139). Dewey’s experimental view of learning has inspired inquiry-based, constructivist, discovery based, and similar pedagogical models of educational practice. Indeed, the theories of educational interaction introduced in unit one and others you will encounter in this course are rooted in Dewey’s conceptualization of learning experience.

The course designer has crafted a course of study and associated active learning experiences in the facilitator’s guide. The course designer’s intent is to lead the student, with the help of your facilitation, through a continuity of interactions leading to positive growth in the learner, as defined by the learning outcomes. As facilitator your role is to help learners navigate this pathway of learning experiences and ensure the intended continuity of learning experiences and the intended learner interactions between the learners and these experiences is achieved.

Every learner and group of learners is unique, each bringing different prior experiences to each new learning situation you will facilitate. So, part of your role is to help learners navigate gaps in continuity and make judgements about what active learning experiences are best suited to helping learners grow.

Topic 2: What Makes a Learning Experience Educational?

As course facilitator you must choose from different activities. You will need to decide which ones will best help each student achieve the course learning outcomes. In some cases, this decision will be based on what activities are most appropriate for a certain group of students, or perhaps even for a particular student. And in other cases, the decision will be necessary because there is not enough time to complete all the activities that have been set out by the course instructor/designer. You will also find yourself in situations that are teachable moments where how you facilitate student learning will have a significant impact on the degree and quality of student transformation. The question this discussion raises is how do you decide what is the best experience to facilitate learning in a given situation? To make good judgements requires a careful understanding of what makes an experience worthwhile.

For many, the concept of education is equivalent with schooling. However, as the American author Mark Twain famously quipped, “don’t let school interfere with your education.” Twain, who was not educated beyond elementary school, was cynical towards the school system, believing that “education” is different from “schooling.” Indeed, he suggested, “Education consists mainly of what we have unlearned.” In other words, education involves the growth and transformation of a whole person. While a school may be a place we learn to read, write, and do arithmetic; to be educated, and hence, to have received an education suggests one becomes something.

In Ethics and Education, educational philosopher R. S. Peters (1966) argues that the term “education” has “normative implications.” That is, it suggests a worthwhile outcome is to be achieved:

It implies that something worth while is being or has been intentionally transmitted in a morally acceptable manner. It would be a logical contradiction to say that a man (sic) has been educated but that he had in no way changed for the better, or that in educating this son (sic) a man (sic) was attempting nothing that was worth while. This is a purely conceptual point. Such a connection between ‘education’ and what is valuable does not imply any particular commitment to content. It is a further question what the particular standards are in virtue of which activities are thought to be of value and what grounds there might be for claiming that these are the correct ones. All that is implied is a commitment to what is thought valuable. (p. 25)

Peters’ (1966) assertion that the term education is more than merely a synonym for learning is surely correct, albeit uninformative. For learning is something that human beings simpley do regardless of whether it is of moral value or not. People naturally learn all sorts of things, including negative attitudes, defensive social skills, and various forms of misinformation, which are counterproductive to one’s identity, purpose, values and goals, or role in society. Thus, while an accurate definition, Barrow and Woods (2006) argue that Peters’ definition leaves two interesting and vitally important questions unanswered, “What are the worthwhile things which are to be transmitted?” and “How do we tell whether a manner of transmission is morally accepted or not?” (p. 30).

The “what” and “how” questions of education take us a step closer to understanding what it means to be educated. Broadly speaking, Peters’ assertion that education involves something of value being learned in a particular way implies that to become educated involves a transformation or a change. That is, to become educated means one becomes something. Consider, our common use of “to educate” in our everyday speech. When we say we must educate someone about something, such as, “We must educate the public” about such-and-such, “the clear implication of this familiar way of speaking is that certain information is to be imparted, this information is to be understood and, in virtue of the understanding, what people do, or do not do, is to change” (Barrow and Woods, 2006, p. 35). Thus, clearly education means not only coming to know such-and-such, but how to do various sort of things.

4.0.1 The Pre-Modern Condition

Educational ideas about what things of worth should be learned and how they should be learned emerge from our theories of knowledge. That is, how one seeks to lead others to know presumes knowledge of what knowledge is and how one comes to have knowledge. Moreover, knowledge is (often, if not always) value laden, making ethical claims on how people ought to live. So, it might also be said that people’s educational ideas about knowledge are informed by their ethical propositions. Lastly, knowledge (typically) is directed at something, which further requires a metaphysical consideration of what there is. Or, in other words, a consideration of the ways in which the known (anything that is) relates to knowledge (what is represented or thought to be). This tri-part conception of knowledge is one we inherited in the West from the ancient Greeks.

Indeed, this way of understanding knowledge and education persisted through Roman times, the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, and remnants remain to this day. The early meaning of the word “education,” reflected this pre-modern condition of thought. The word arrives in the English language in the mid 16th century from the Latin term educatio, from the verb educare, with the stem educo, meaning 1) to draw out, lead out, or 2) to bring up, raise, rear, educate. The first thing that you might find interesting about this etymology is that the theory and practice of education and leadership have always been related to each other. That is, education from its earliest conception education involved leading others. What may not, at first, be apparent is the original meaning of the idea of “drawing” out, or “leading” out, that finds its formative source in antiquity.

In Meno, Plato gives this formative, if not the first, written account of the ancients’ educational notion of “leading out.” Plato described how Socrates engaged in dialogue with Meno’s slave, where he demonstrated to Meno that his slave is capable of learning a geometrical truth, because “his soul … always possessed this knowledge.” Put in the context of Plato’s broader dialogue, the text Meno begins with the character Meno asking Socrates if virtue can be taught? Socrates responds by asking Meno to define what is virtue? Then, using what has come to be known as the Socratic method—that is, asking Meno question after question to help him critically understand his thinking by exposing flaws in his logic and reasoning, followed by encouraging him to refine his theories, and ultimately helping him arrive at a tenable conclusion—Socrates brings Meno to the question: What is knowledge? The answer, which Socrates uses Meno’s slave to demonstrate, is that one is not taught, but rather only recollects knowledge from past lives. That is, knowledge is innate—one possesses a priori knowledge—and we learn by remembering what we already know, but didn’t yet know that we knew it. Put simply, education involves “drawing forth” knowledge from within the person.

It is important to note that the ancients did not view this form of knowledge from within that one could draw out as a “subjective” form of knowledge, as we might now interpret this idea. Rather, it was an “objective and universal” truth that existed within one’s soul.

This idea persisted, and by late antiquity Augustine, in his dialogue On the Teacher, still presents a similar concept of education when he writes, “Concerning universals of which we can have knowledge, we do not listen to anyone speaking and making sounds outside ourselves.” However, as a Christian he reframes this old idea slightly, suggesting that “We listen to Truth which presides over our minds within us.” For Augustine, this Truth within each person is Christ who he considers to be the real Teacher. This real Truth within is like light that allows people to discern things; in so much as we are able. This reframed idea was common through the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, and in the context of Christian education various forms of this revised idea are still present today.

This idea of “drawing forth” knowledge remains an important concept for use, as in part, it forms a foundation to how we understand the roles of coaching learners and facilitating learning experiences.

4.0.2 The Modern Condition

Following, the classical tri-part conception of what one ought to know and how one comes to know, typical of ancient through the Middle Ages thought, a new modern condition of thought emerged. In the mid-17th century, the seeds of the Enlightenment (and more broadly speaking, the Modern Era) were planted by Descartes’ Discourse on Method, published in 1637, and by Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica in 1687. These two conceptual insights mark redactions of two longstanding Western thought traditions and together generate a new education paradigm. Ways of thinking inspired by Plato’s ideal Forms and Aristotle’s normative ideals were supplanted (respectively) by Descartes’ method of rightly conducting reason (philosophic positivism) and Newton’s system of mathematical physics (scientific method). Consequently, (and irrespective of any deductive or inductive distinction) the pre-modern “organic” paradigm of intellectual coherence shifted into a modern “mechanical” one. This new paradigm of learning introduced a now commonplace “constructivist” model of knowledge, which is at once, still modern and is presently shifting into something that is “beyond” that definition.

Regarding the modern condition, Doll (1993) writes, “the metaphor of mind shifted from being an abstract quality of the soul to being a ‘thing’ in the body” (p. 113). Descartes made a fundamental distinction between the materiality of body and the non-materiality of the mind — res extensa (the physical world) and res cogitans (the thinking being). The epistemological significance of this division was a shift from realism to idealism. Put differently, it was a shift from “object” knowledge that exists independent of the subject’s mind (objectivism) towards “object” knowledge that exists only within the subject’s mind (subjectivism). While not altogether a new idea Descartes’ mind-body split was unique in that he articulated a bidirectional relationship between these two realms. That is, while the mind was understood to be the body’s rational controller, so to, the body was seen to influence the mind’s otherwise rational control. The historical fallout for education was the development, in modern times, of two competing views of mind—behaviorism and cognitivism—in addition to the privileged place of “Positivism” over all other forms of knowing the world and coping with its challenges.

Newton’s contribution to the modern condition of thought was his view of Nature and its order—that is, its “uniformity” and “simple symmetry; and buried within that symmetry … a set of necessary, linear, causative relations accessible to exact mathematical description” (Doll, 1993, p. 34). Under Newton’s purview, the world, and its “events, activities, experiences,” became “quantified” (p. 35) and its future events became predictable. Taken together, Descartes and Newton signaled a conceptual shift in what we understand knowledge to be, and how we might best acquire it. The answer to what is worthwhile in education changed—that is, our conception of education became scientific.

Responding to the first of the two essential education question we raised above—What knowledge is of most worth?—Herbert Spencer (1896) writes, “the uniform reply is—Science” (p. 93). After systematically considering a broad and diverse array of worthwhile human knowledge Spencer makes the following summary and conclusion:

For direct self-preservation, or the maintenance of life and health, the all important knowledge is—Science. For that indirect self-preservation which we call gaining a livelihood, the knowledge of greatest value is—Science. For the due discharge of parental functions, the proper guidance is to be found only in—Science. For that interpretation of national life, past and present, without which the citizen cannot rightly regulate his conduct, the indispensable key is—Science. Alike for the most perfect production and highest enjoyment of art in all its forms, the needful preparation is still—Science. And for purpose of discipline—intellectual, moral, religious—the most efficient study is, once more—Science. (pp. 93-94).

While today Science in education is commonplace, in Spencer’s day his complaint was that science, which he considered “of such transcendent value” actually “received the least attention” (p. 95) within education. Nevertheless, scientific and Positivist thinking did, in fact, widely permeate modern thought. In Descartes method of right reason, and Newton’s scientific method we looked to build a secure understanding of our world. As a result of these methods of thought new ideas, such as, Hegel’s description of history as dialectical process, or Marx’s description of economic development in social-cultural terms, or Spencer description of progressive social development as a process of social evolution began to shape our thinking and our education. A collective vision emerged to bringing the world into one moment of time, culture, economy, and political system. However, the viability of this project came to be seen as an ever more impossible goal.

In modern times, the old idea of teaching as a helping act leading a student to discover the Truth through their own act of study, transformed in a directive act of instructing the learning. That is, teachers become instructors, and students became learners. The hope of scientific education was twofold. First, we thought that if we could understand how people learn, then, we could understand how to instruct them in their learning. Metaphorically, we saw people as learning “machines” who could be “programmed” with instructions, just like we program computers. Second, we believed science could give us secure, reliable Truth, which we could then program our minds to hold. The problem is that people are not machines, and scientific knowledge is not secure.

4.0.3 The Post-Modern Condition

Simply put, while science was an incredibly powerful way of understanding the natural world, it was less successful at describing or more importantly predicted the social world. Jean-François Lyotard described this dissolution with the limits of science to know the world, the post-modern condition. Lyotard’s primary interest is the high-status knowledge produced by the social institutions of highly developed (Western) societies. In his seminal work The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge (Lyotard, 1984) he notes that a primary characteristic of this type of knowledge production is a modern notion that aspires to fit all forms of knowledge into a general unifying narrative. Lyotard designates any knowledge (in particular scientific) as modern that “legitimates itself with reference to a metadiscourse of this kind making an explicit appeal to some grand narrative, such as the dialectics of Spirit, the hermeneutics of meaning, the emancipation of rational or working subject, or the creation of wealth” (1984, p. xxiii).

Lyotard’s contention with scientific knowledge is that it makes unifying appeals to grand metadiscourses. And, that in so doing it limits our sensitivity to the totality of true knowledge rather than serving to encompass it. That is, these grand narratives hold the appearance of making the complex easier to understand, but in actuality they desensitizes us to the world’s true complexity and the language games inherent in the narratives themselves. Consequently, he defines the “postmodern as incredulity toward metanarratives” (1984, p. xxiv). This is not to say that narratives are not an important knowledge form, but rather that “helpful” narratives tend to be local in nature (local sense-making to achieve local aims) and cannot be simply linked together into a general unifying scheme. Thus, we might summarize that the “postmodern condition is characterised by the co-existence of a multiplicity of heterogeneous discourses—a state of affairs assessed differently by different parties” (Cilliers, 1998, p. 114). For our discussion of education, this means that this is not one truly unified theory of education, or knowledge, or teaching, or even human learning.

As Lyotard illustrates, “instead of trying to analyse complex phenomena in terms of single or essential principles,” postmodern approaches to thinking “acknowledge that it is not possible to tell a single and exclusive story about something that is really complex” (Cilliers, 1998, p viii). Consequently, the richness, complexity and diversity of the emerging postmodern perspectives has served to diminished the power of traditional modern discourses, which sought “to deliver a universal identity, sense of direction and historically assured destination” (Fry, 1999, p. 64). Likewise, as a “critical reappraisal of modern modes of thought” (Waters in Doll, 1993, p. 5) it’s fair to say that on the whole the postmodern condition has served to engender a greater flexibility of thinking within many domains, including education. However, it must also be noted that the diversity and contradictions of modernity that postmodern thinking brings to light were ever present in modernity itself, only they were repressed by our initial idealism or hidden from view prior to being institutionalized.

As educators today, we have inherited a mix of classical, modern, and now post-modern ideas about education, knowledge, teaching, and learning. In short, educators, including adult educators, draw upon a diverse plurality of ideas about their practice. Moreover, learners, including adult learners have been shaped by different educational approaches. These thinking frameworks lie beneath all our discussions.

Topic 3: Study as the Site of Education

Learning ultimately occurs within the cognitive presence of individual learners, through their personal interactions with their self and the content. Historically, this educational experience has been widely understood as the practice known as study. McClintock (1971/2000) argues, “whether we like it or not, many … educators considered education to consist of neither teaching nor learning; instead, they found the diverse forms of study to be the driving force in education” (p. 167). While instruction in all of its various forms may play a role, the learner is always the one who does the work of learning. Citing Montaigne’s (1877) essay “Of the Education of Children” McClintock (1971/2000) notes, “teaching and learning might impart knowledge, whereas study led to understanding, whereby things known were made one’s own and became a part of one’s judgment, and ‘education, labor, and study aim only at forming that’” (p. 162). Here, we see how Dewey’s notion of the importance of learners adding their own meaning and application to what they learn connects to a thread of thought with a long history. We also see the educational idea of the normative or ethical element of whole personal transformation.

What is study?

The term comes into English as a shortening of the Old French noun estudie, and its verb form estudier, both based on the Latin term studium. This is also the root of the Latin word student. Cicero provides us with a formative use of the term in De Inventione:

*Studium est autem animi assidua et vehementer ad aliquam rem applicata magna cum voluntate occupatio, ut philosophiae, poeticae, geometricae, litterarum” [“Study is the assiduous and vehement occupation of the mind applied to anything with great eagerness (voluntate), as the study of philosophy, geometry, letters.”* (as translated in O’Malley, 1881, p. 269)] (1.36).

Cicero’s notion of study turns on the idea that it is an “occupation” of the mind, specifically, mental work that has to be done, or matters of the mind that have to be attended to. Moreover, study, here, is a careful application of this mental attention to a subject of inquiry. Indeed, study is an act of considerable labour as Erasmus (1965) writes in his dialogue The Art of Learning, “For my part, I know no other art of learning than hard work, devotion, and perseverance” (p. 461). As educators tasked with coaching others for learning and facilitating learning experiences it is important to be clear that ultimately it is the student who must do the actual work of learning. Indeed, regardless of how much help we as educators can provide students with their learning, learning is often difficult work. Therefore, a significant role that you play is to help by encouraging students to do this challenging task.

Cicero’s definition also suggests study is a zealous act of pleasure. He argues study is not merely the laboured devotion of time and attention to acquiring knowledge on a given subject, but rather a passionate pursuit of knowledge. Commenting on Cicero’s definition, O’Malley (1881) writes,

Whatever we strongly love we desire to possess, and if we see any probability of our efforts being crowned with success, we strain every nerve to make it our own. So intense is the pleasure of the votaries of knowledge as she unfolds and offers them her treasures, that labour ceases to be labour, or, if you will, becomes a labour of love, and receives a name which indicates its agreeable nature. (p. 269)

Pleasure, here, is not limited only to a life of leisurely study, as was historically most commonly enjoyed by those who were, or were amongst, the elites, but rather is at its heart an act of utility to win self-control through self-formation. That is, study is historically the domain of what we now refer to as transformational learning. This transformational act of study may take many forms. As McClintock (1971/2000) puts it,

“the ways of study are as diverse as the ways of men (sic), for both result, not from conformity to outward precept, but from the aspiration to assert inward control over the moving conjunction between one’s self and one’s circumstances” (para. 13).

While the highest goal of study—such as, Plato’s pursuit of the “Good,” or Aristotle’s human “flourishing”—may be the same, or similar, “the path, the course of study, that leads to the goal will differ for each: thus the study appropriate for the quite cleric will not suit the proud prince, the worldly merchant, or the study artisan” (para. 14). Study emerges from the particular and unique lifeworld or lived-experience of those individuals who study—that is, the subjective human interests of students. As educators coaching for transformational learning, part of our role is to help students identify and clarify what interests them. What is more, we can help students connect their interests with their course of study and help them find joy in learning.

How does one study?

For McClintock (1971/2000), “study itself is neither a single path nor the final goal; it is the motivating power by which men (sic) form and impose their character upon their role in life” (para. 14). That is, study is an act of transformation and growth. Pinar (2006) helpfully adds that McClintock’s the use of “the verb ‘impose’ is too voluntarist and essentialist” because transformational learning or “reinvention of ourselves is limited, and occurs, yes, through acts of ‘will,’ but, as well, through waiting, withdrawing, dissimulation” (p. 112). Historically, transformational learning was seen as the outcome of study—that is, learning was the result of study. Similarly, the historic idea of teaching was simply helping a student to study. Underlying this historic view of study as education was the recognition of human individuality, autonomy, and creativity. On this point, McClintock (1971) writes:

To those who thus recognized each person’s autonomy of judgment, education could only incidentally be a process of teaching and learning; more essentially, it had to be a zig-zag process of trial and error, of studious, self-directed effort by which an inchoate, infantile power of judgment slowly gave itself form, character, perhaps even a transcendent purpose. This effort was study in its most general sense. (p. 168)

Building upon the idea of study as self-formation is the student’s subjective habit of making sense of the world and finding their own way in it. It is a movement of thought characterized by Pinar’s (1975b, 2004) conception of currere, a running within the learner’s own lived-experiences. Understood as currere, study is a subjective act of structuring an objective world, upon which the learner imposes their own idiosyncratic subjectivity, which this world, then, embodies as their world of thought (Grumet, 1975). It is an attentive and open dialogue with the world of the learners lived-experience made possible by human language, which makes study discursive. As the dialogue with the learner’s lived-experience study is a reflective act where the learner both reflects in and on their experience (Schön, 1983). Through study, the learner prepares for future action by using their experience of the past. They reflect on present action, building upon what they already know. And, they consider what they don’t know, or what they think they know but don’t really, to estimate emerging opportunities, and predict future action by imagining the impossible and determining new capabilities. Study, writes Pinar (2015), “provides that knowledge from which we exercise judgment, as we reflect not only on the possible consequences of that step we’re about to take next, but the effects of steps that we have taken before” (p. 192). As an educator who is coaching students in their own study, your role is to help them develop their own judgement as they reflect in and on the learning experiences set out in their course of study. More importantly, you are helping navigate a dialogue with themselves about who they are becoming.

As educators coaching students for transformational learning our overarching aim is to help students make sense of how to reflect in and on the converging and emerging of their past, present, and future. How does this work? Pinar (2015) characterizes this self-transformational that is study as follows:

The unforeseeable future, the not fully accessible present, as well as the persistence of the past, converge to contribute to the gravity of study, even when it is conducted playfully. Study acknowledges the mystery saturating everyday life, thereby decentering the self as it redirects our attention to reality in which we live. Steadied through study we can reactivate the past in the present, unsettling our sense of what is at stake in the situation we face today and tomorrow. Studying the past permits us to anticipate the future. Not only temporality structures study, so does space, as the boundaries of one’s world blur into the world, which we know extends well beyond our capacity to apprehend it. (p. 192)

Bound by a space and a time, study is a particularity, not a generality. Study is embodied in individual lives, it is a place and situation “saturated by meaning, with culture and history as these are personified in specific people with whom we live as neighbors, fellow citizens, and humanity” (Pinar, 2015, p. 192). The act of study as defined by McClintock and Pinar is not something, which is limited to a formal program of study. Rather, McClintock and Pinar remind us all of culture, and nature, can be educational. Going back to antiquity, Hutchins (1968, p. 133) notes that “education was not a segregated activity,” but rather as was the situation in Greece, “the Athenian was educated by culture, by paideia” (p. 33). The critical insight to emerge, here, is that “study is the site of education” (Pinar, 2006, p. 112). The nature of study is a very personal, often difficult, potentially joyous, dialogue of self-transformation. As educators, our ultimate role is to help others in their personal acts of study and self-transformation.

Topic 4: Institutionalization of Teaching and Learning

In his essay “Towards a place for study in a world of instruction” McClintock (1971/2000) observes how the modern era’s institutionalization of study progressively led to a fundamental shift in practice:

Rarely does one hear that study is the raison d’etre of an educational institution; teaching and learning is now what it is all about, and with this change, has come a change in the meaning of the venerable word “learning.” Once it described what a man acquired as a result of serious study, but now it signifies what one receives as a result of good teaching. The psychology of learning is an important topic in educational research, not because it will help students improve their habits of study, but because it enables instructors to devise better strategies of teaching. (p. 179).

The institutionalization of study begins as the story of how education begins through family relations. Grumet (1988) argues, “what is most fundamental to our lives as men and women sharing a moment on this planet is the process of reproducing ourselves” (p. 8). The critical insight, here, is that as human beings we reproduce ourselves biologically, ideologically and critically. While familial learning practices have histories beyond memory or record, we may infer from accounts of foraging societies that “the youth [were] trained to practice the arts which their parents [knew], to continue their friendships and alliances, and to cherish their resentments” (Williams, p. 19). Studies of juveniles in hunting and gathering societies, as well as in lower primates social groups, suggest there was “little teaching (that is, direct and deliberate tuition) of the younger members by mature individuals” (Herzog, 1984, p. 74).

Rather, learning in the distant past was a socialization process, predominately in the form of “play” with “peers and slightly older playmates” involving “imitative activities” of “competent behavior” being observed within the context of the local “social and physical environment” during a “period of freedom from responsibility and of the need for self-support” that was “unusually long” compared to other species (Herzog, 1984, pp. 75-74). This process of learning through indirect (social role-modelling) and direct teaching in family relations continues today in the pre-school years of children.

Western institutions of study first appear within the context of ancient Greek society. The Greek system was based on both informal familial and community schooling, along with formal schooling in the form of private tutors or schools for those of economic means. The existence of formal schooling in early antiquity, however, does not mean it was commonplace. Indeed, the primary institutional form of education was the family and community. In ancient Athens, as noted in the previously:

[E]ducation was not a segregated activity, conducted for certain hours, in certain places, at a certain time of life. It was the aim of the society. The city educated the man. (Hutchins, 1968, p. 133)

The ancient person was educated first by family and then, by culture (that is, paideia). One’s familial and cultural relations largely defined the ancient life-world of study. However, as these ancient societies—notably, Greek city-states—rationalized, becoming states and nations defined by laws and rules, institutional systems of study emerged to support the reproduction of increasingly complex forms of social order.

Plato (2003) cast a formative vision of this institutionalized world of study:

By maintaining a sound system of education and upbringing you produce citizens of good character; and citizens of sound character, with the advantage of a good education, produce in turn children better than themselves and better able to produce still better children in turn, as can be seen with animals. (p. 125)

While Plato’s idea had little affect in his own time, clearly, the shadow that his idea has cast upon the future is significant. Indeed, we might argue that Plato planted an ancient seed that became our modern idea of progress cast, here, within the context of formalized education. Closely related to his idea of progress, and progress in a society’s institutionalization of study is Plato’s notion of the “good.” The good is a central element of Plato’s theory of knowledge, his vision of a just society and individual, and the purpose of his system of education (that is, his institutional view of study). Plato’s pithy definition of the good comes near the end of the Republic when he compares the concept with that of evil by stating, “I call anything that harms or destroys a thing evil, and anything that preserves and benefits it good” (Plato, 2003, p. 355). His definition appears to be straightforward and clear, but it raises questions about what precisely does he have in mind by “anything that preserves and benefits” a thing? In social terms, his “Good” relates to the preservation and benefit of the whole community. For the individual, it relates to the preservation and benefit of a person’s mind/soul as a whole.

For Plato, development of the good is made possible through study. Specifically, it is the individual’s upward progress of the mind from the lower world of shadows and opinions towards the upper world of light and knowledge. Beyond what we can know lies the “Good,” which is distinct from knowledge, and yet it is through knowledge that one can come closest to the “Good.” While Plato’s epistemology is clearly more complicated, the important insight for our current discussion is that Plato established the subsequently persistent idea that study is directional, and that it is oriented toward seeking ends. That is, study is an educative experience that results in a person becoming educated. The way we began to formalize how someone could become educated was through the idea of a “course” of study.

The Course of Study

Within educational institutions a course of study, or simply a course, is generally referred to the curriculum. Interestingly, these two education terms, course and curriculum, are closely related. As Egan (1978) explains, the initial Latin meaning of the word curriculum “was ‘a running,’ ‘a race,’ ‘a course,’ with secondary meanings of a ‘race-course,’ ‘a career.’” (p. 66). What is curriculum? Put simply, it is “what is to be taught and how” (Alexander, 2001, p. 549). Framed broadly, “curriculum communicates what we choose to remember about our past, what we believe about the present, what we hope for the future” (Pinar, 2004, p. 20). Dewey provides us with a helpful analogy about the curriculum as both a map and a journey. That is, his map image describes curriculum as a plan and his journey image described curriculum as a lived experience. Dewey’s main point is to caution us against mistaking the map for the journey; however, he also recognized the crucial role the map plays in this journey.

Explaining the important role of the map Dewey (1902) writes:

Well, we may first tell what the map is not. The map is not a substitute for a personal experience. The map does not take the place of an actual journey. The logically formulated material of a science or branch of learning, of a study, is no substitute for the having of individual experiences. The mathematical formula for a falling body does not take the place of personal contact and immediate individual experience with the falling thing. But the map, a summary, an arranged and orderly view of previous experiences, serves as a guide to future experience; it gives direction; it facilitates control; it economizes effort, preventing useless wandering, and pointing out the paths which lead most quickly and most certainly to a desired result. Through the map every new traveler may get for his own journey the benefits of the results of others’ explorations without the waste of energy and loss of time involved in their wanderings–wanderings which he himself would be obliged to repeat were it not for just the assistance of the objective and generalized record of their performances. That which we call a science or study puts the net product of past experience in the form which makes it most available for the future. It represents a capitalization which may at once be turned to interest. It economizes the workings of the mind in every way. Memory is less taxed because the facts are grouped together about some common principle, instead of being connected solely with the varying incidents of their original discovery. Observation is assisted; we know what to look for and where to look. It is the difference between looking for a needle in a haystack, and searching for a given paper in a well-arranged cabinet. Reasoning is directed, because there is a certain general path or line laid out along which ideas naturally march, instead of moving from one chance association to another. (p. 284)

The learning design and its associated documents that we create as educators constitute a map of the terrain to be covered within a course of study (that is, a learning program). Nevertheless, it is important to recognize it is not an exhaustive view of the territory, but simply sets directive guidance for the teachers’ and students’ journey through this terrain. In short, curricular documents, like a syllabus, simply serves as the guide to the learning experience. As educators, we shouldn’t be bound to it. In our role of coaching and facilitating transformational learning our role is to acts as guides in the curricular journey that students are undertaking and they work to complete a particular course of study.

Topic 5: Emerging Models of Open and Multi-Access Education

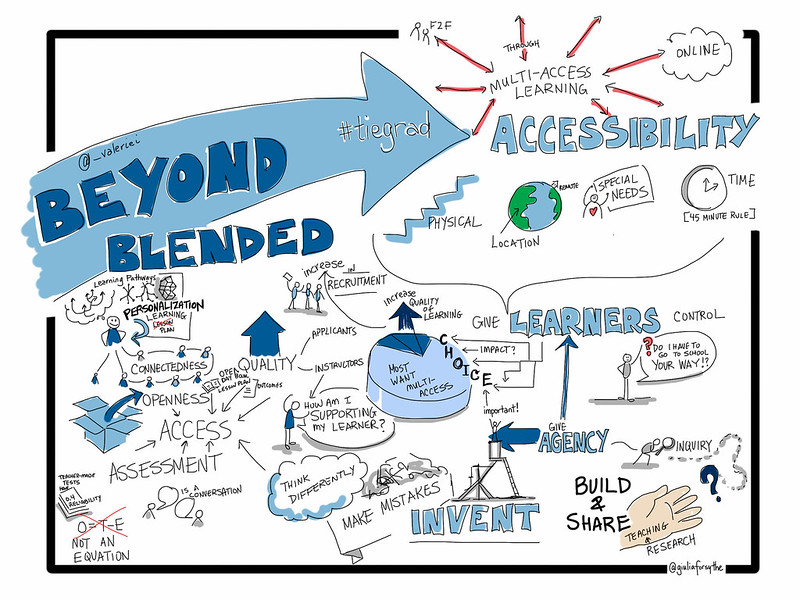

Online learning, blended learning, flipped classroom, face-to-face, hybrid course, multi-access… you may have heard some of these terms tossed around, especially recently with the shifting focus to online. Before we unpack and examine these modalities of learning, consider how learning in Higher Education has changed. What are the shifts that have happened in the last 20, 10, 5 years? How has technology shaped the way teachers teach and the way students learn?

Topic 6 - Multi-Access Learning Environments

One trend that is gaining traction is Multi-Access Learning.

Read the following excerpt from Realigning Higher Education for the 21st-Century Learner through Multi-Access Learning by Irvine, Code & Richards (2013):

Multi-access learning is an opportunity to meet both student needs for access to learning experiences and faculty needs for graduate student recruitment (Irvine, 2009; Irvine & Code, 2011, 2012; Irvine & Richards, 2013). Irvine defines multi-access learning as a framework for enabling students in both face-to-face and online contexts to personalize learning experiences while engaging as a part of the same course. Multi-access learning is different than blended learning because it places the student at the center of the learning experience as opposed to the instructor or the institution.

Further, “blended learning” is a problematic term due to its multiple interpretations in the literature and in daily practice, leaving one to ask, “Who controls the blend?” When and where the face-to-face sessions occur and when and how the online synchronous or asynchronous sessions occur are often controlled in blended learning settings. At the core, the institution or instructor is in control of the blend, no matter the configuration.

Multi-access learning, however, has the learner at the center, with the ability to choose how he/she wants to access the course. The core principle of the multi-access framework is one of enabling student choice in terms of the combination of course delivery methods through which the learning environment is accessed; that is, each individual learner decides how he/she wishes to take the course (e.g., face-to-face or online) and can then participate with other students and the instructor – each of whom have their own modality preferences – at the same time” (Irvine, Code & Richards, 2013).

Source: Tiers of the multi-access framework (Irvine, Code & Richards, 2013).

With the uncertainty brought on by COVID-19, multi-access learning has great potential for our education system. This modality not only brings more choice to students, but promotes a learner-centred course design and best practices in teaching and learning.

The 4 tiers of multi-access learning:

4.0.3.0.1 Tier 1

The first tier of multi-access learning is what most of you have experienced (as learners and faculty) as the predominant modality of higher education, face-to-face (f2f). F2f learning environments are often assumed to be the preferred modality of learning because a f2f classroom allows for rich, multi-modal interactions and robust community-building. This is true to an extent, but only if class sizes are very small; large, lecture-based classrooms present significant challenges to building the kind of critical and safe community for engaged interaction.

4.0.3.0.2 Tier 2

The second tier of access allows learners who cannot travel to a central campus (like during a worldwide pandemic) to participate in a learning community syncronously via video conferencing. Remote and local learners may exchange items and artifacts and may share video feeds and use software such as Etherpad or screensharing through the web-conferencing tool to collaborate on documents for co-creation of content.

4.0.3.0.3 Tier 3

The third tier provides asynchronous access for remote learners who cannot join the scheduled class session due to any number of constraints (employment, child/elder care, time-zone, or even network bandwidth). Irvine, et al. acknowledge that simply viewing a recording of a synchronous session, regardless of how collaborative and engaging that session may have been, is a much leaner experience for learners and may not be optimal. This highlights the need to provide learning materials in formats beyond video and audio, perhaps including text-based materials and asynchronous tools for co-creation of content such as GitHub.

4.0.3.0.4 Tier 4

The outermost tier of the model is for open participation from non-credit learners who are choosing to participate for their own interest and edification. It may seem anathema to some faculty to consider opening their course to the world, but the benefits can be significant, particularly in times like the spring of 2020.

Learning Activities